[ad_1]

| Venue: Edgbaston Date: 1 July Time: 18:35 BST |

| Coverage: Live on BBC Two, BBC iPlayer and the BBC Sport website and app from 18:00 BST. Ball-by-ball Test Match Special commentary on BBC Sounds, BBC Radio 5 Live and the website and app, where there will be live text commentary and in-play video clips (UK only) |

England will go into the T20 series against Australia in the Women’s Ashes with no left-handed batters in their 16-player squad.

It is a continuing trend, with a lack of options available to head coach Jon Lewis and captain Heather Knight.

It leaves a “huge gap” in England’s skillset says Lewis, with a combination of left and right-handers often picked so bowlers are unable to get into a rhythm and batters can capitalise on any short boundaries.

BBC Sport have worked with data analysts CricViz to crunch the numbers and work out if the issue is isolated to England.

What do the numbers say?

According to research about 10% of the population are left-handed, with a BBC Newsround article in 2022 saying numbers were thought to be between 10-12%.

Therefore you would assume England would have about that percentage of left-handers in their squad at any given time, right?

Wrong.

Since 1 April 2016, and the retirement of multiple World Cup winner Lydia Greenway, who scored more than 4,000 runs in 225 internationals, England have had just two left-handed batters.

In Test matches it is none from 17, and then two from 29 and 31 in one-day internationals and T20s respectively – 6.9% and 6.45% if converted.

The non-England women’s average per year over the same time period is 16.94%, with the following table showing how many left-handed women the main nations have selected.

| Team | Tests | ODIs | T20s |

| England | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Australia | 5 | 8 | 7 |

| India | 3 | 8 | 7 |

| South Africa | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| New Zealand | N/A | 2 | 2 |

| West Indies | N/A | 10 | 10 |

| Sri Lanka | N/A | 14 | 14 |

| Pakistan | N/A | 6 | 6 |

| Bangladesh | N/A | 1 | 2 |

| Ireland | N/A | 3 | 2 |

While England struggle to produce left-handers, they are not necessarily alone in the women’s game.

It is a problem we can isolate to the women’s game in this country, with the men’s side having had 21 left-handed batters in the same period.

The glaring disparities start to show themselves when you consider the roles of left-handers in each women’s side.

England’s pair of Freya Kemp and Tash Farrant are an all-rounder and bowler so generally have very little influence with the bat.

They have also only played seven ODIs and 19 T20s between them in the time period.

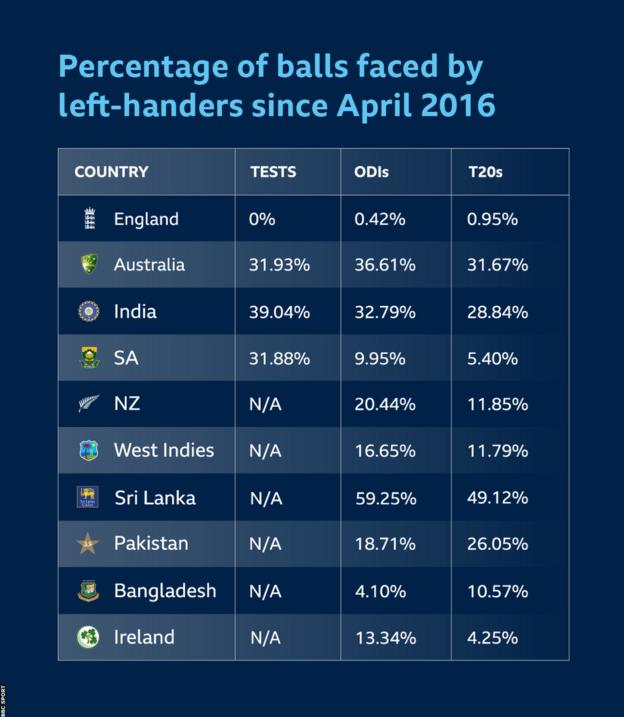

If we look at the following graphic, we can see England’s left-handers are facing nowhere near as many balls in each format as any other nation.

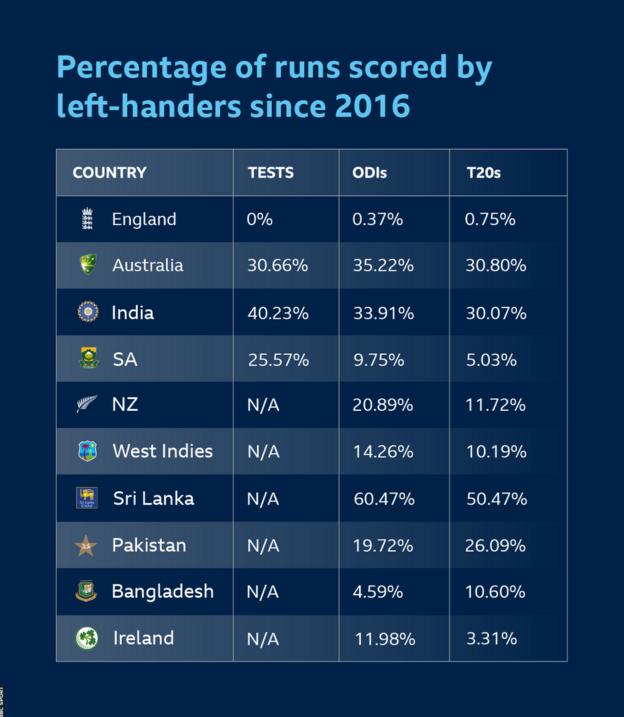

It is a similar picture when you consider runs scored by left-handers in the same period, as shown in the graphic below.

As expected there is a clear correlation between balls faced and runs scored with similar numbers, and positional ordering, across the 10 teams included.

England’s left-handers have faced 84 balls in ODIs, scoring 58 of their 16,620 runs, with Bangladesh at 290 balls and 161 runs the next lowest.

It is a similar picture in T20s with England’s pair having only faced 82 balls, scoring 79 of their 8,641 runs. The next lowest is Ireland’s 272 balls faced and 207 runs scored.

Sri Lanka dominate both tables with left-handers scoring 73 times more ODI runs than England (4,281 of 7,080) by left-handers, and 38 times more T20 runs (2,992 of 5,928).

In the women’s game we are starting to see a big three – England, Australia and India – dominate, and England sit well behind both in terms of balls faced and runs scored.

In ODIs, Australia’s left-handers have faced 6,197 deliveries (73 times more), with India’s coming in at 6,721 (80 times more). It is a similar picture in T20s with 2,479 and 3,050 (30 and 37 times more) respectively.

Perhaps the best comparison is with New Zealand, who have also only fielded two left-handers in the time period, but they are both recognised batters in Amy Satterthwaite and Brooke Halliday.

In ODIs that pair have faced more than 43 times as many balls as England’s pair (3,613 to 84), and scored almost 51 times as many runs (2,945 to 58).

It is similar in T20s with the Kiwi pair facing 10.5 times as many balls (861 to 82), and scoring almost 12 times as many runs (941 to 79).

While England are comparable with some nations in terms of players involved, they are not producing top-six batters, where the bulk of the scoring is done, particularly in the white-ball formats which dominate the women’s game.

‘It’s a real issue for us’

In white-ball cricket left and right-hand batting combinations are often spoken about because it can put a bowler off their line and length.

One of the side boundaries can occasionally be shorter than the other too, so having a varied batting line-up allows you to target one.

Not having that option could potentially hamper England.

“It is definitely something I’ve noticed, 100%,” Lewis, who was appointed in November, told BBC Sport.

The former bowler, who played one Test and 15 white-ball games for England, also highlighted how the lack of options means their bowlers are not getting to practise against left-handers.

Australia have two left-handers in Beth Mooney and Phoebe Litchfield at the top of the order and Lewis said it was a “real issue” for England, who used male youth players in the build-up to the series to help prepare their bowlers without disrupting the women’s domestic game.

It was a feeling England’s all-time leading wicket-taker Katherine Sciver-Brunt shared.

“It is really irritating bowling to a left and right-hand combination,” she said. “Putting it in the right spot for a right-hander one ball and then a left-hander next ball is extremely difficult and a skill in itself.

“It is not just about running in every ball, everything is not the same. How you would hold the ball in your hand would probably change, the angle which you’d run in would probably change, the things that you tell yourself – your key words – would change slightly.

“If you’re having to do that every ball it is very difficult and it becomes so hard to create pressure, because to figure someone out you need to have them at the crease for three or four balls and let them see the differences you’re presenting and work it out from there.”

However, despite their concerns about bowling to left-handers, their bowlers’ dot-ball and boundary percentage is similar to Australia’s and India’s.

| Tests | ODIs | T20s | ||||

| Team | RHB | LHB | RHB | LHB | RHB | LHB |

| England | 76.3 | 78.6 | 61.6 | 58.2 | 48.5 | 43.3 |

| Australia | 73.9 | 75.9 | 59.2 | 57.7 | 45.2 | 42.1 |

| India | 75.5 | 79.3 | 55.8 | 54.3 | 43.0 | 43.9 |

| Tests | ODIs | T20s | ||||

| Team | RHB | LHB | RHB | LHB | RHB | LHB |

| England | 7.4 | 5.8 | 7.8 | 8.6 | 11.6 | 13.9 |

| Australia | 6.0 | 8.2 | 6.4 | 6.9 | 12.5 | 13.8 |

| India | 5.8 | 1.7 | 8.7 | 7.2 | 14.3 | 12.9 |

Do other teams see it as an advantage?

England men’s white-ball coach Matthew Mott used to coach Australia women, guiding them to a 50-over World Cup success and two T20 titles.

Australia’s ability to field left-handers was always a “huge advantage” according to Mott.

“We always picked the best team, and we were just fortunate to have a couple of left-handers in there,” Mott told BBC Sport.

“With small boundaries a lot of the time, having the option to send a left-hander in to make the most of it was always a huge bonus for us.

“In the World Cup final in 2022, we made a definite move of utilising Beth [Mooney] to take on a bowler like Sophie Ecclestone, who has an unbelievable record. But we knew that if there was a weakness, even a slight one, it was against left-handers. Beth went out and changed the game and disrupted her.”

Is there a reason for England’s lack of options?

One possible theory for England’s lack of options – and potentially generally across the women’s game – is hockey.

It is a sport only played with right-handed sticks, with the vast majority of left-handed players switching.

Cricket-playing nations also excel at hockey with England, Australia and India winning the medals in both the men’s and women’s 2022 Commonwealth Games, and New Zealand joining England and Australia on the podium in the 2018 edition.

“I don’t know why [it is an issue],” said Lewis. “I don’t really have an answer as to why.

“I know a lot of golf coaches turn young players round from left to right because it’s a lot easier to coach the way you play, so I’m wondering if right down to the moment of the pathway, when young girls are being taught how to play cricket, they get turned around to play right-handed because it is a lot easier for the coach.

“My suggestion to anyone out there who does pathway coaching at a young age is please don’t turn people around. If they want to bat left-handed please let them bat left-handed because it is a huge gap in our game.”

Is there anyone who could come in?

One possible left-handed option for England in the coming years will be Grace Scrivens.

The 19-year-old led England in the Under-19 World Cup this year and is set to captain England A in the ODIs against their Australia counterparts.

“I am a bit weird,” said Scrivens. “I am right-handed. I play golf left-handed but everything else – tennis, any racquet sport – right-handed.

“My dad always tells me the story that I was a pain as a kid and he would be ‘pick it up right-handed’, and I would say ‘no, I want to do it this way’ and would continuously pick it up the other way, maybe to frustrate him, maybe because I wanted to do it my way.

“It is helpful for me 100%, but whether it will massively help I am not sure.”

Lewis and England will be hoping more children follow Scrivens’ stubbornness to bat left-handed and the generational gap starts to close, and assist England, in the coming years.

By Callum Matthews

Source link