[ad_1]

England enduring a miserable time at the Cricket World Cup is nothing new.

Amid the disappointment and dejection that usually arrives on a quadrennial basis, there is an episode that sticks out as one of the biggest sport-meets-politics controversies of modern times.

The row England became embroiled in 20 years ago started over the morality of playing a game in Zimbabwe and involved death threats, the cancellation of the match and, ultimately, their exit from the tournament.

It is reasonably straightforward to describe the situation English cricket found itself swallowed up by in February 2003.

Though the World Cup was essentially being held in South Africa, matches were also being staged in Zimbabwe and Kenya.

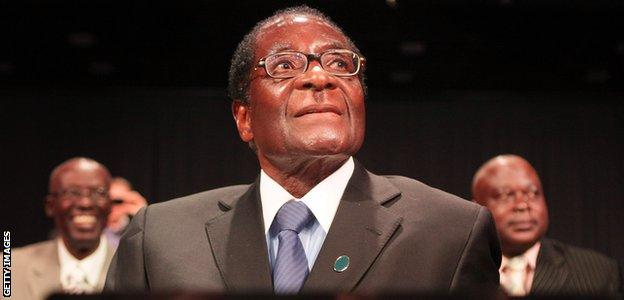

Tony Blair’s government did not want the England team to travel to Zimbabwe for their group game against the co-hosts because of Robert Mugabe’s ruling regime, but stopped short of ordering a boycott.

The England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB), mindful of the ramifications if the fixture was not fulfilled, was keen for it to go ahead.

That left the 15 players and rest of the staff in the squad caught in the middle, wrestling with the rights and wrongs of playing the game, at the same time knowing whichever decision they came to could have serious, possibly even deadly, consequences.

Locked in discussions at the Cullinan Hotel in Cape Town, they went round in circles.

“We’d been in the room at the hotel for three days discussing it and went out for breakfast,” Nasser Hussain, England captain at the time, tells BBC Sport.

“Muttiah Muralitharan, the great Sri Lanka spinner, grabbed me and said: ‘What’s the discussion? Just play in Zimbabwe.’

“I looked at him as if to say, ‘it’s not an issue for Sri Lanka, but it’s definitely an issue for us’.

“Sometimes politics and sport do clash, and this was one of those occasions.”

What were the politics?

The significance of a team from Great Britain travelling to Zimbabwe is rooted in the relationship between the two countries.

Zimbabwe gained independence in 1980, but by the time of the World Cup was going through great political and economic instability. Thousands of white farmers were forced from their land, often violently, in 2000 and 2001.

During Zimbabwe’s opening game of the World Cup against Namibia, Andy Flower and Henry Olonga famously wore black armbands to “mourn the death of democracy” in their country.

“Mugabe had said some very strong things about British politicians,” says Olonga. “He would routinely attack Tony Blair for the war in Iraq. He was very eloquent. He spoke forthrightly about Great Britain and not always in glowing terms.”

In the run-up to the World Cup, the ECB had signed a contract with the International Cricket Council (ICC) that bound it to sending a full-strength team to fulfil all fixtures.

In the eyes of the ICC, only reasons of safety and security would cause a game to be moved or abandoned. For anything else, the punishment for not playing would be a fine, or even exclusion from the global game.

However, as the tournament drew nearer, the British government gradually increased the pressure on England not to play. Crucially, though, there was no guarantee of compensation to the ECB if it received a fine, or if Zimbabwe pulled out of a planned tour to England the following summer.

“The government and politicians knew perfectly well this fixture was due to take place, yet they left it to the very last minute,” says Tim Lamb, then the ECB chief executive.

“At that time, British airlines were flying in on a daily basis. There were hundreds of British companies trading with Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe was still a member of the Commonwealth and there was no international sporting boycott. Why were we singled out?

“The government refused to say ‘you cannot go’ or countenance any suggestion of financial compensation if we didn’t go. The participating nations’ agreement was quite clear. Unless there were genuine safety and security grounds, or a team was forbidden by government to fulfil a fixture, there was no other acceptable excuse.

“Obviously we had misgivings about the regime in Zimbabwe. It was totally abhorrent. I was well aware of what was going on, but we had a contractual obligation to fulfil that fixture.”

‘There were some very drained and teary cricketers’

Just as the British government was making its feelings clear, England were taking a typically one-sided hammering in an Ashes series in Australia.

The Zimbabwe issue came to the forefront of Hussain’s mind on that tour, with England due to head straight to the World Cup. For the England squad, including a 20-year-old James Anderson barely out of club cricket at Burnley, preparing for the biggest event in the sport took a back seat to discussing an issue way beyond the remit of a professional cricketer.

“Usually in World Cups you’ll do your nets and practice, maybe play a match, then you’ll be around the pool and the video games would come out,” says Hussain.

“We’d go back to the hotel, and at 6pm every night we’d be back in that room again to discuss it. There were some very drained cricketers and there were few tears in there.

“When you get the job of England captain, you know it isn’t just choosing whether to bat or bowl. You are an ambassador for your country. I didn’t want to represent our country at that time in Zimbabwe, for the people of Zimbabwe more than anything else.

“But that wasn’t for everyone in the team. Some people believed sport and politics shouldn’t mix. I had to bear that in mind. It was all well and good me wanting to take a stand, but some just wanted to play cricket because that was their job. Intertwining all of this stuff to make a decision was what made it confusing.”

The ECB asked for the match to be switched to South Africa – a request rejected by the ICC.

Hussain and the England team held a heated meeting with ICC chief executive Malcolm Speed, and Hussain and coach Duncan Fletcher, himself Zimbabwean, had secret discussions with Flower and Olonga.

The idea of England travelling to play the fixture and staging some sort of protest, perhaps wearing black armbands of their own, was mooted but discarded.

In his autobiography, published in 2004, Hussain described the episode as the “most traumatic time of my life”. He also detailed the reservations of some players about pulling out, with both Alec Stewart and Ronnie Irani making the case for the game to go ahead.

‘You will go home in wooden coffins’

When the final vote came, the squad were unanimous in not travelling on moral grounds. Only at that moment did a potential way out of the whole mess present itself.

Some months before, while England were in Australia, the ECB received a threat from a group calling itself the Sons and Daughters of Zimbabwe. It said: “Come to Zimbabwe and you will go back to Britain in wooden coffins.”

The players were not told until the last moment, when security advice to take threat seriously filtered through.

“I was pretty sure, and remain to this day pretty sure, that it was a hoax,” says Lamb.

Hussain shares reservations about its validity, but was not in a position to take a chance.

“I couldn’t say ‘don’t worry, it’s a hoax’,” he says. “Probably 999 times out of 1,000 you get it right, but that one time you get it wrong…

“This isn’t like bowling Jimmy Anderson one over too many. When there are death threats to the team and their family, you can’t say ‘this could be a hoax’, you have to take it seriously.

“When some of the team saw it, they took it seriously. If we hadn’t made any fuss, I don’t think that letter would have emerged.”

Lamb visited Speed and told him England would not fulfil the fixture on security grounds, though in reality the players had decided they would not have travelled anyway. Still, the death threat was not enough to convince the ICC that England had grounds to pull out. The game did not take place and the four points were awarded to Zimbabwe.

“I didn’t want to go, but I’m England captain and we wanted to get points to qualify for the next stage of the World Cup,” says Hussain.

“I’m trying to convince the ICC and the ECB if there is something in the rules the only way the game can be called off is safety and security and we are getting death threats, that strikes me as safety and security.

“If we can use that to not go, fine. If I had been given the choice of what would I have liked to done, I would have said I am not going to Zimbabwe for reasons other than safety and security.”

Even then, England could have made it out of their group. They contrived to lose a game they should have won against eventual champions Australia and were ultimately undone by a washout in the game between Pakistan and Zimbabwe that sent Zimbabwe through.

Hussain resigned as one-day captain after England were knocked out, and was done as Test captain a few months later. The following year, he retired.

“Looking back, am I proud as England captain I didn’t go to Zimbabwe at that stage? Yes,” he says.

“Would I have been even more proud had I done it the right way, like Flower and Olonga? Definitely. Did we fudge it? Yes.”

Ultimately, the on-field consequences were as bad as it got for the ECB. There was no fine from the ICC, no expulsion and Zimbabwe played two Tests in England later in 2003.

England even undertook a tour of Zimbabwe in 2004 – Kevin Pietersen’s debut – though that trip highlighted the close connection between cricket and politics in the country. A five-match ODI series was cut to four games when travelling UK journalists struggled to gain entry to Zimbabwe.

BBC cricket correspondent Jonathan Agnew, who covered the 2003 World Cup and 2004 tour, says: “We were in Johannesburg and got word we could finally travel, so got the last flight to Harare.

“We arrived late at night, and got to passport control. A man had a list with my name on it. I said: ‘That’s good news.’ He said: ‘No, it’s bad news. Go and stand over there.’ I was with Peter Baxter, then the Test Match Special producer, and he was on the list.

“They were going to take us to the cells and deport us in the morning. I had the number of Peter Chingoka, the chief executive of Zimbabwe Cricket, in my phone. I called him and said: ‘Peter, your tour is about to be called off.’

“It just showed how intricately connected everything was, because it took about two minutes for an official to take us away and allow us into the country.”

As for Olonga and Flower, the consequences of England’s decision were much more important. Zimbabwe’s passage through the group stage took them to the next phase of the tournament in South Africa.

For the two players who had made their public protest against the government, it was a route to freedom.

“I was able to escape into exile,” says Olonga.

“I tip my hat to Nasser Hussain and the boys because they got the decision right. You have to look yourself in the mirror. Having a clear conscience that you stood up for human rights must give you a sense of something.

“I really should have bought him a beer. Maybe the next time I bump into him, I will.”

By Stephan Shemilt

Source link